Sound (nada) is believed to be the heart of the process of

creation. In Hinduism, the sacred syllable Om embodies the

essence of the universe - it is the "hum" of the

atoms and the music of the spheres - and sound in general

represents the primal energy that holds the material world

together. Nada Brahma is a primal word in Indian spirituality, a

primal word that also refers to India's great classical music. Since the most ancient times, music in India has been practiced

as a spiritual science and art, a means to enlightenment.

Sangita, which originally meant drama, music and dance, was

closely associated with religion and philosophy. At first it was

inextricably interwoven with the ritualistic and devotional side

of religious life. The recital and chant of mantras has been an

essential element of vedic ritual throughout the centuries.

According to Indian philosophy, the ultimate goal of human

existence is moksha, liberation of the atman from the

life-cycle, or spiritual enlightenment; and nadopasana

(literally, the worship of sound) is taught as an important

means for teaching this goal. The highest musical experience is

ananda, the “divine bliss.” This devotional approach to

music is a significant feature of Indian culture.

The origin of Indian

music is enshrined in beautiful tales and legends. It is common

Hindu practice to attribute the beginning of a branch of

learning to a divine origin through the agency of a rishi.

Shiva, also called Nataraja, is supposed to be the creator of

Sangita, and his mystic dance symbolizes the rhythmic motion of

the universe.

Curt Sachs (1881-1959) who

played the leading role among early modern scholars in the field

organology -- the study of musical instruments and their musical

and cultural contexts, has said, that the South Indian drum

tambattam that was known in Babylonia under the name of timbutu,

and the South Indian kinnari shared its name with King David's

kinnor. Arrian, the biographer of Alexander, also mentions that

the Indian were great lovers of music and dance from earliest

times.Sir Yehudi Menuhin (1916-1999), American-born

violinist, one of the foremost virtuosos of his generation, has written:

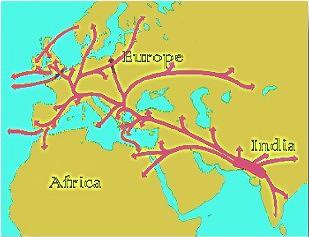

"We would find all, or most, strands

beginning in India; for only in India have all possible modes

been investigated, tabulated, and each assigned a particular

place and purpose. Of these many hundreds, some found their way

to Greece; others were adopted by nomadic tribes such as the

Gypsies; others became the mainstay of Arabic music. Indian

classical music, compared with our Western music, is like a pure

crystal. It forms a complete perfected world of its own, which

any admixture could only debase. It has, quite logically and

rightly, rejected those innovations which have led the

development of Western music into the multiple channels which

have enabled our art to absorb every influence under the sun.

Freedom of development in Indian music is accorded the

performer, the individual, who, within fixed limits, is free to

improvise without any restraint imposed externally by other

voices, whether concordance or discordant - but not to the basic

style, which exclude polyphony and modulation."

Author Claude Alvares has said, that the Indian system of talas, the rhythmical time-scale of Indian

classical music, has been shown (by contemporary analytical

methods) to possess an extreme mathematical complexity. The

basis of the system is not conventional arithmetic, however, but

more akin to what is known today as pattern recognition.

Indian

music is art nearest to life. That is why Irish poet William Butler Yeats

(1856-1939) a 1923 Nobel Laureate in Literature, has aptly described

Indian music "not an art but life itself."

Introduction

History of Music

The

Origins of Hindu Music

The

Antiquity of Indian Music

The Development of Scale

The Nature of Sound

Raga - The Basis of Melody

Tala

or Time Measure

Musical Instruments

and Sanskrit

Writers on Music

Some

Ancient

Musical Authorities

Raga and Jazz

Colonialist

thinking of Indian music

Views about Hindu music

Mantras

Conclusion

Introduction

"Even if

he be an expert in the Revealed and the traditional scriptures,

in literature and all sacred books, the man ignorant of music is

but an animal on two feet."

"He who

knows the inner meaning of the sound of the lute, who is expert

in intervals and in modal scales and knows the rhythms, travels

without effort upon the way of liberation.

- (Yajnavalkya Smriti III, 115).

Sound (nada) is believed to be the

heart of the process of creation. In Hinduism, the

sacred syllable Om embodies

the essence of the universe - it is the "hum" of

the atoms and the music of the spheres - and sound in general

represents the primal energy that holds the material world

together. Sangita, the Indian tradition of music, is an old as Indian

contacts with the Western world, and it has graduated through

various strata of evolution: primitive, prehistoric, Vedic,

classical, mediaeval, and modern. It has traveled from temples

and courts to modern festivals and concert halls, imbibing the

spirit of Indian culture, and retaining a clearly recognizable

continuity of tradition. Whilst the words of songs have varied

and altered from time to time, many of the musical themes are

essentially ancient.

The music of India is one of the oldest unbroken musical

traditions in the world. It is said that the origins of

this system go back to the Vedas (ancient scripts of the

Hindus). Sangita, which originally meant drama, music and dance, was

closely associated with religion and philosophy. At first it was

inextricably interwoven with the ritualistic and devotional side

of religious life. The recital and chant of mantras has been an

essential element of Vedic ritual throughout the centuries.

According to Indian philosophy, the ultimate goal of human

existence is moksha, liberation of the atman from the

life-cycle, or spiritual enlightenment; and nadopasana

(literally, the worship of sound) is taught as an important

means for teaching this goal. The highest musical experience is

ananda, the “divine bliss.” This devotional approach to

music is a significant feature of Indian culture.

The Indian

music tradition can be traced to the Indus (Saraswati) Valley

civilization. The goddess of music, Saraswati, who is also the

goddess of learning, is portrayed as seated on a white lotus

playing the vina.

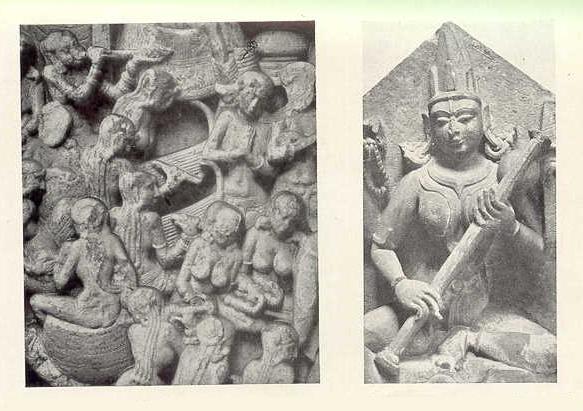

Bow-harps

and Flutes - Amaravati A.D. 200. - Vina in the

hands of Goddess Saraswati

(image source: The Legacy of India - edited by G. T.

Garrett).

***

Alain

Daneliou a.k.a

Shiv Sharan (1907-1994), son of

French aristocracy, author of numerous books on philosophy,

religion, history and arts of India, including Virtue,

Success, Pleasure, & Liberation : The Four Aims of Life in

the Tradition of Ancient India. He

was perhaps the first European to boldly proclaim his Hinduness.

He settled in India for fifteen years in the study of Sanskrit. In Benaras Daniélou

came in close contact with Karpatriji Maharaj, who inducted him

into the Shaivite school of Hinduism and he was renamed Shiv

Sharan. After leaving Benaras, he was also the director of

Sanskrit manuscripts at the Adyar Library in Chennai for some

time. He returned to Europe in 1960s and was associated with

UNESCO for some years

.While

in Europe, Daniélou was credited with bringing Indian music to

the Western world. This was the era when sitar maestro Ravi

Shankar and several other Indian artists performed in Europe and

America. During his years in India, Daniélou studied Indian

music tradition, both classical and folk traditional, and

collected a lot of information from rare books, field

experience, temples as well as from artists. He also collected

various types of instruments.

Alain Daniélou was

credited with bringing Indian music to the Western world.

Watch

Raga

Unveiled:

India

’s Voice – A film

The history and essence of North Indian classical Music

***

He

has written:

"Under the name of

Gandharva

Vedas, a

general theory of sound with its metaphysics and physics appears

to have been known to the ancient Hindus. From such

summaries: The

ancient Hindus were familiar with the theory of sound (Gandharva

Veda), and its metaphysics and physics. The

hymns of the Rig Veda contain the earliest examples of words set

to music, and by the time of the Sama Veda a complicated system

of chanting had been developed. By the time of the Yajur

Veda, a

variety of professional musicians had appeared, such as lute

players, drummers, flute players, and conch blowers."

The origin of Indian music is enshrined in beautiful tales

and legends. It is common Hindu practice to attribute the

beginning of a branch of learning to a divine origin through the

agency of a rishi. Shiva, also called Nataraja, is supposed to

be the creator of Sangita, and his mystic dance symbolizes the

rhythmic motion of the universe. He transmitted the knowledge of

cosmic dance to the rishi Bharata, through one of his ganas.

Tandu. The dance is called tandava and Bharata thus became the

first teacher of music to men, and even to apsaras, the heavenly

dancers. Similarly, the rishi Narada, who is depicted as

endlessly moving about the universe playing on his vina (lute)

and singing, is believed to be another primeval teacher of

music.

Buddhist

texts also testify to the prevalence of Sangita, both religious

and secular, in early India. Music in India, however, reached

its zenith during the Gupta

period,

the classical age of the Indian art and literature.

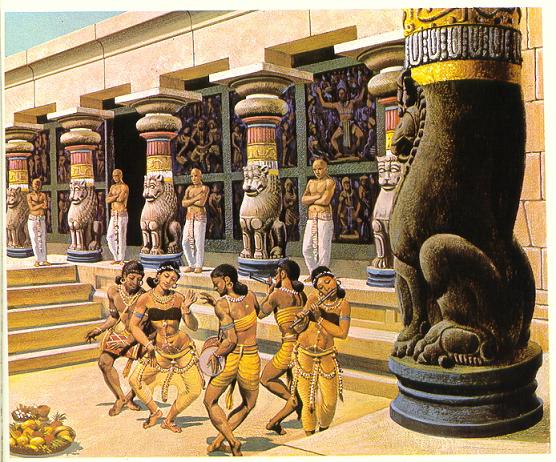

Music

in India, however, reached its zenith during the Gupta Empire,

the classical age of the Indian art and literature.

(image

source: Early

Civilization: Universal History of the World – By John

Bowman volume

I Golden Press.

New York

. Published in 1966. p. 75).

***

Indian

music is based upon a system of ragas and is improvised or composed at

the moment of performance. The notes which are to convey certain definite

emotions or ideas are selected with extreme care from the twenty-five intervals

of the sruti scale and then grouped to form a raga, a mode or a melodic

structure of a time. It is upon this basic structure that a musician or singer

improvises according to his feeling at the time. Structural melody is the most

fundamental characteristic of Indian music. The term raga is derived from

Sanskrit root, ranj or raj, literally meaning to color but figuratively meaning

to tinge with emotion. The essential of a raga is its power to evolve

emotion. The

term has no equivalent in Western music, although the Arabic

maqam iqa corresponds to it.

Oversimplified, the concept of raga is to connect musical ideas

in such a way as to form a continuous whole based on emotional

impact. There are, however, mixed ragas combined in a continuous

whole of contrasting moods. Technically, raga is defined as

"essentially a scale with a tonic and two axial

notes," although it has additional characters.

Musical notes

and intervals were carefully and mathematically calculated and

the Pythagorean Law was known many centuries before Pythagoras

propounded it. They were aware of the mathematical law of music.

(source: India:

A synthesis of cultures – by Kewal Motwani p.

78-95).

The word raga

appears in Bharata's

Natyasastra, and a similar concept did

exist at the time, but it was Matanga (5th century) who first

defined raga in a technical sense as "that kind of sound

composition, consisting of melodic movements, which has the

effect of coloring the hearts of men." This definition

remains valid today. Before the evolution of the raga concept in

Bharata's time, jati tunes with their fixed, narrow musical

outlines constituted the mainstay of Indian music. These were

only simple melodic patterns without any scope for further

elaboration. It was out of these jati tunes that a more

comprehensive and imaginative form was evolved by separating

their musical contents and freeing them from words and metres.

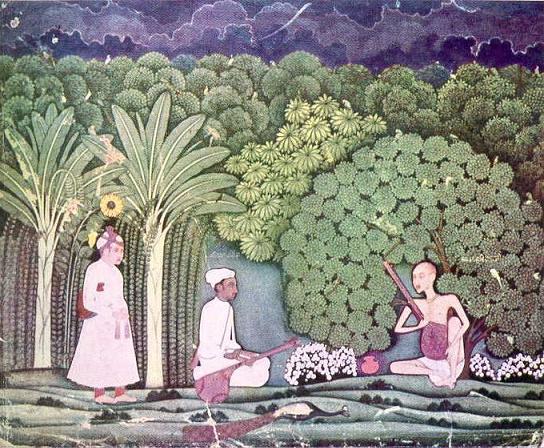

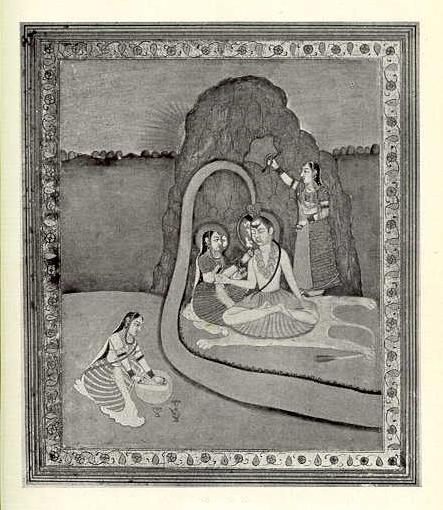

Music lessons.

(image

source: The Splendor that was India -

By K T Shah p. 116).

***

Indeed a raga is

basically a feeling, the expression of which has come to be

associated with certain notes and twists of melody. A musician

may compose in the same raga an indefinite number of times, and

the music can be recognized in the first few notes, because the

feelings produced by the musician's execution of these notes are

intensely strong. The effect of Indian music is cumulative

rather than dramatic. As the musician develops his discourse in

his raga, it eventually colors all the thoughts and feelings of

the listeners. Clearly, the longer a musician can dwell on and

extend the theme with artistic intensity the greater the impact

on the audience.

Alain

Danielou (1907-1994)

head of the

UNESCO Institute for Comparative Musicology wrote:

""Unlike

Western music, which constantly changes and contrasts its moods,

Indian music, like Arabic and Persian, always centers in one

particular emotion which it develops, explain and cultivates,

upon which it insists, and which it exalts until it creates in

the hearer a suggestion almost impossible to resist. The musician, if he is sufficiently skilled, can "lead his

audiences through the magic of sound to a depth and intensity of

feeling undreamt of in other musical systems."

(source: Northern

Indian Music -

By Alain Danielou Praeger, 1969

p. 115).

Dr.

Ananda Coomaraswamy

has written: "Indian music is essentially impersonal,

reflecting "an emotion and an experience which are deeper

and wider and older than the emotion or wisdom of any single

individual. Its sorrow is without tears, its joy without

exultation and it is passionate without any loss of serenity. It

is in the deepest sense of the word all human." Dr.

Ananda Coomaraswamy

has written: "Indian music is essentially impersonal,

reflecting "an emotion and an experience which are deeper

and wider and older than the emotion or wisdom of any single

individual. Its sorrow is without tears, its joy without

exultation and it is passionate without any loss of serenity. It

is in the deepest sense of the word all human."

(source: The

Dance of Shiva - By Ananda Coomaraswamy

p. 94).

It is an art nearest to life; in fact, W.

B. Yeats

called

Indian music,

"not an art, but life itself,"

although its theory is elaborate and technique difficult.

The possible

number of ragas is very large, but the majority of musical

systems recognize 72 (thirty-six janaka or fundamental, thirty

six janya or secondary). New ragas, however, are being invented

constantly, as they have always been, and a few of them will

live to join the classical series. Many of the established ragas

change slowly, since they embody the modes of feeling meaningful

at a particular time. It is for this reason that it is

impossible to say in advance what an Indian musician will play,

because the selection of raga is contingent upon his feelings at

the precise moment of performance.

Indian music

recognizes seven main and two secondary notes or svaras.

Representing definite intervals, they form the basic or suddha

scale. They can be raised or lowered to form the basic of suddha

scale. They can be raised or lowered to form other scales, known

in their altered forms as vikrita. The chanting of the Sama Veda

employed three to four musical intervals, the earliest example

of the Indian tetrachord, which eventually developed into a full

musical scale. From vaguely defined musical intervals to a

definite tetrachord and then to a full octave of seven suddha

and five vikrita was a long, continuous, and scientific process.

For instance, Bharata's

Natyasastra, the earliest surviving work

on Indian aesthetics variously dated between the second century

B.C. and the fourth century A.D., in its detailed exposition of

Indian musical theory, refers to only two vikrita notes, antara

and kakali. But in the Sangita

Ratnakara,

an encyclopedia of Indian music attributed to Sarngadeva

(1210-1247), the number of vikritas is no less than nineteen;

shadja and panchama also have acquired vikritas. It was during

the medieval period that Ramamatya

in the south, and Lochana-kavi

in the north in his Ragatarangini

refered to shadja and panchama as constant notes. Indian music

thus came to acquire a full fledged gamut of mandra, madhya, and

tar saptak.

The scale as it

exists today has great possibilities for musical formations, and

it has a very extensive range included in the microtonal

variations. The microtones, the twenty-two srutis, are

useful for determining the correct intonation of the notes,

their bases, and therefore their scales (gramas). The Indian

scale allows the musician to embellish his notes, which he

always endeavors to do, because grace plays the part in Indian

music that harmony does in European music.

Whilst Indian

music represents the most highly evolved and the most complete

form of modal music, the musical system adopted by ore than

one-third of mankind is Western music based on a highly

developed system of harmony, implying a combination of

simultaneously produced tones. Western music is music without

microtones and Indian music is music without harmony. The

strongly developed harmonic system of Western music is

diametrically opposed in conception and pattern to the melodic

Indian system. Harmony is so indispensable a part of Western

music today that Europeans find it difficult to conceive of a

music based on melody alone. Indians, on the other hand, have

been for centuries so steeped in purely melodic traditions that

whilst listening to Western music they cannot help looking for a

melodic thread underlying the harmonic structures.

Flying Gandharvas and Apsaras.

Indian musical

instruments are remarkable for the beauty and variety of their

forms, which the ancient sculptures and paintings in caves of

India have remained unchanged for the last two thousand years.

(image

source: The Splendor that was India -

By K T Shah p. 115).

***

The fundamental

and most important difference between the European and Indian

systems of rhythm is respectively one of multiplication and

addition of the numbers two and three. The highly developed tala,

or rhythmic system with its avoidance of strict metre and its

development by the use of an accumulating combination of beat

subdivisions, has no parallel in Western music. On the other

hand, the Indian system has no exact counterpart to the tone of

the tempered system, except for the keynote, of Western music.

Consequently, just and tempered intonations are variously

conceived which eliminate the possibility of combining the

melodic interval theory of the sruti system with the Western

modulating, harmonic, arbitrarily tempered theory of intervals.

With its tempered basis, larger intervals, and metred rhythms,

Western music, is more easily comprehended than Indian music,

which seems to require a certain musical aptitude and ability to

understand its use of microtones, the diversification of the

unmetred tala, and the subtle and minutely graded inflection.

Western music, as

it appears today, is a relatively modern development. The

ancient Western world was aware of the existence of a highly

developed system of Indian music. According

to Curt

Sachs (1881-1959)

author of The

History of Musical Instruments

(W W Norton & Co ASIN 0393020681) it was the South Indian drum tambattam that was known in

Babylonia under the name of timbutu, and the South Indian

kinnari shared its name with King David's kinnor, Strabo

referred to it, pointing out that the Greeks believed that their

music, from the triple point of view of melody, rhythm, and

instruments, came to them originally from Thrace and Asia.

Arrian, the biographer of Alexander,

also mentions that the

Indians were great lovers of music and dance from earliest

times. The Greek writers, who made the whole of Asia, including

India, the sacred territory of Dionysos, claimed, that the

greater part of music was derived from Asia. Thus, one of them,

speaking of the lyre, would say that he caused the strings of

the Asian cithara to vibrate. Aristotle describes a type of lyre

in which strings were fastened to the top and bottom, which is

reminiscent of the Indian type of single-stringed ektantri vina.

Curt Sachs considers India the possible source of eastern rhythms, having the oldest history and one of the most sophisticated rhythmic development.

It is probably no accident that Sanskrit, the language of India, is one in which there is no pre-determined accent upon the long and short syllables; the accents are determined by the way in which it falls in the sentence. Sanskrit developed in the first thousand years B.C. Each section of the ancient holy book, the

Rigveda, has a distinct rhythm associated with each section so that the two aspects are learned as one.

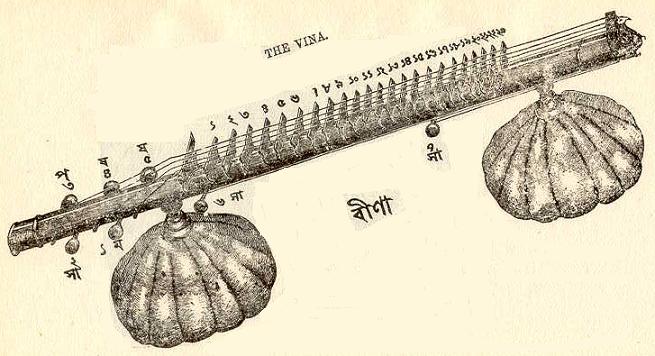

The ancient

Vina: This

one instrument alone is sufficient evidence of the development

to which the art had attained even in those early days.

***

The vina is really neither a lute

nor a harp, although it is commonly translated in English as

lute. Generally known in its construction as bow-harp, the vina

must have originally been developed from the hunting bow, a type

of musical bow, pinaka, on which a tightly drawn string was

twanged by the finger or struck with a short stick. To increase

the resonance a boat-shaped sound box was attached, consisting

of a small half-gourd of coconut with a skin table or cover,

through which a bamboo stick was passed longitudinally, bearing

a string of twisted hair resting on a little wooden bridge

placed on the skin table. This was the ekatari, or one-stringed

lute of India, which soon produced its close relative, the

dvitari or two-stringed lute. Later, additional strings were

inevitably added. Whilst it is possible to trace the passage of

the slender form of the fingerboard instrument, pandoura, from

Egypt to Greece, it was not until they came into contact with

the Persians that the Greeks became acquainted with the bow, a

fact which may reinforce the view of the Indian origin of the

Greek lute.

Although many varieties of the

vina have been evolved, it existed in its original form, now

extinct, in the vedic and pre-vedic times. This is known from

the excavations at Mohenjodaro and Harappa. There is sufficient

evidence that some of these musical instruments were constructed

according to the heptatonic, sampurna, scale with seven notes.

However, in the other contemporary civilizations of Egypt and

Mesopotamia, similar instruments have been found. The vina is

often shown in the hands of the musicians on the early Buddhist

sculptures at Bhaja, Bharhut, and Sanchi and is still in use in

Burma and Assam. In Africa, it is used by many Nilotic tribes. A

bow-barp, known as an angle-harp, closely resembling the Indian

vina can be seen in the mural paintings at Pompeii.

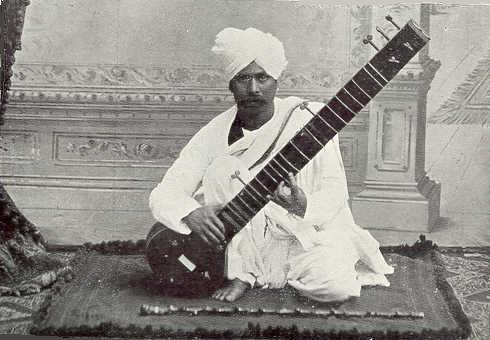

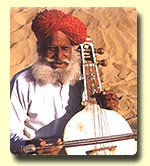

A

professional sitar player.

(image source: The

Splendor that was India - By K T Shah p. 116).

***

The two earliest Greek scales,

the Mixolydic and the Doric, have an affinity to early Indian

scales. Some recent British writers, for example the editors of

The New Oxford History of Music, have attempted to exclude

Indian influence by making the somewhat strange suggestion that

the term "India" meant countries much nearer. Whilst

the evidence pointing to the direct influence of India on Greek

interest in Indian art. In addition, there are parallels between

the two systems, which may or may not be connected. It

is certainly true that the seven note scale with three octaves

was known in India long before the Greeks were familiar with it.

Pythagoras scheme of cycle of the fifth and cycle of the fourth

in his system of music is exactly the same as the sadjapancama

and saja-madhyama bhavas of Bharata. Since

Bharata lived several centuries after Pythagoras, it has been

suggested that he borrowed the scheme from Pythagoras. At the

same time it has been pointed out that Indian music, dating as

it does from the early Vedic period, is much anterior to Greek

music, and that it is not unlikely that Pythagoras may have been

indebted to Indian ideas. In almost all other fields of

scholarship in which he was interested, a close identity between

his and the older Indian theories has already been noted.

Whilst no title of any Sanskrit

work on music translated at Baghdad is available, there

is not doubt that Indian music influenced Arab music.

The well-known Arab writer Jahiz,

recording the popularity of Indian music at the Abbasid Court,

mentions an Indian instrument known as kankalah, which was

played with a string stretched on a pumpkin. This instrument

would appear to be the kingar, which is made with two gourds.

Knowledge of Indian music in the Arab world is evidenced by an

Arab author from Spain, who refers to a book on Indian tunes and

melodies. Many technical terms for Arab music were borrowed from

Persia and India. Indian music, too, was influenced in return,

incorporating Persio-Arab airs, such as Yeman and Hiji from

Hijaz. At the beginning of their rise to power, the Arabs

themselves had hardly any musical system worth noting and mainly

practiced the existing system in the light of Greek theory.

Since Indian contact with western Asia had been close and

constant, it would appear likely that the Arabic maqam iqa is

the Persian version of the Indian melodic rhythmic system, traga

tala, which had existed for more than a thousand years before

maqam iqa was known.

Yehudi

Menuhin (1916-1999) had one of the longest and most

distinguished careers of any violinist of the twentieth century.

He was convinced that: Yehudi

Menuhin (1916-1999) had one of the longest and most

distinguished careers of any violinist of the twentieth century.

He was convinced that:

""We would find all, or most, strands

beginning in India; for only in India have all possible modes

been investigated, tabulated, and each assigned a particular

place and purpose. Of these many hundreds, some found their way

to Greece; others were adopted by nomadic tribes such as the

Gypsies; others became the mainstay of Arabic music. However,

none of these styles has developed counterpoint and harmony,

except the Western-most offshoot (and this is truly our title to

greatness and originality), with its incredible emotional impact

corresponding so perfectly with the infinite and unpredictable

nuances, from the fleeting shadow to the limits of exaltation or

despair, or subjective experience. Again, its ability to paint

the phenomena of existence, from terror to jubilation, from the

waves of the sea to the steel and concrete canyons of modern

metropolis, has never been equalled."

(source:

Indian and Western Music - Yehudi

Menuhin / Hemisphere, April 1962, p. 6.).

"Indian

music has continued unperturbed through thirty centuries or more,

with the even pulse of a river and with the unbroken evolution of

a sequoitry."

(source:

The

Music of India - By Peggy Holroyde

p. 119).

Peter

Yates (1909 -1976) music critic, author,

teacher, and poet, was born in Toronto, had reason when he said

that “Indian music, though its theory

is elaborate and its technique so difficult, is not an art, but

life itself.”

(source: The

Dance of Shiva – by A K Coomaraswamy p. 79-60).

"Despite

predisposition in India's favor, I have to acknowledge that Indian

music took me by surprise. I knew neither its nature nor its

richness, but here, if anywhere, I found

vindication of my conviction that India was the original

source."

"Its

purpose is to unite one's soul and discipline one's body, to make

one sensitive to the infinite within one, to unite one's breath of

space, one's vibrations with the vibrations of the cosmos."

(source:

Unfinished

Journey - By

Yehudi Menuhin

p. 250 - 268).

Top

of Page

History

of Music

The beginnings

of Indian music are lost in the beautiful legends of gods and

goddesses who are supposed to be its authors and patrons. The

goddess Saraswati is always

represented as the goddess of art and learning, and she is

usually pictured as seated on a white lotus with a vina, lute,

in one hand, playing it with another, a book in the third hand

and a necklace of pearls in the fourth.

The technical

word for music throughout India is the word sangita, which

originally included dancing and the drama as well as vocal and

instrumental music. Lord Shiva is supposed to have been the

creator of this three fold art and his mystic dance symbolizes

the rhythmic motion of the universe. The technical

word for music throughout India is the word sangita, which

originally included dancing and the drama as well as vocal and

instrumental music. Lord Shiva is supposed to have been the

creator of this three fold art and his mystic dance symbolizes

the rhythmic motion of the universe.

In Hindu

mythology the various departments of life and learning are

usually associated with different rishis and so to one of these

is traced the first instruction that men received the art of

music. Bharata rishi is said

to have taught the art to the heavenly dancers - the Apsaras -

who afterwards performed before Lord Shiva. The Rishi Narada,

who wanders about in earth and heaven, singing and playing on

his vina, taught music to men. Among the inhabitants of Indra's

heaven we find bands of musicians. The Gandharvas are the

singers, the Apsaras, the dancers, and the Kinnaras performers

on musical instruments. From the name Gandharva has come the

title Gandharva Veda for the art of music.

Among the early

legends of India there are many concerning music. The

following is an interesting one from the Adbuta Ramayana about

Narada rishi which combines criticism with appreciation.

"Once upon

a time the great rishi Narada thought himself that he had

mastered the whole art and science of music. To curb his pride

the all-knowing Vishnu took him to visit the abode of the gods.

They entered a spacious building, in which were numerous men and

women weeping over their broken limbs. Vishnu stopped and

enquired of them the reason for their lamentation. They answered

that they were the ragas and the raginis, created by Mahadeva;

but that as a rishi of the name of Narada, ignorant of the true

knowledge of music and unskilled in performance, had sung them

recklessly, their features were distorted and their limbs

broken; and that, unless Mahadeva or some other skillful person

would sing them properly, there was no hope of their ever being

restored to their former state of body. Narada, ashamed ,

kneeled down before Vishnu and asked to be forgiven."

Vedic

Music

It is a matter

of common knowledge to all music lovers that Indian classical

music has its origin in the Sama Veda. Yet the singing of the

Sama Veda has practically disappeared from India. What is heard

nowadays is sasvara-patha and not sasvara-gana, that is to say,

only musical recitation of the Sama Veda, not its actual

singing.

Top

of Page

“animals tamed or wild, even children, are charmed by

sound. Who can describe its marvels?” (Sang. Darp. I-31).

Under the name of Gandharava Veda,

a general theory of sound with its metaphysics and physics

appears to have been known to the ancient Hindus. From such

summaries as have survived till modern times, it seems that the

properties of sound, not only in different

musical forms and systems but also in physics, medicine,

and magic. The rise of Buddhism with its hostility towards

tradition brought about a sharp deviation in the ancient

approach to the arts and sciences, and their theory had often to

go underground in order to avoid destruction. It was at this

time that the Gandharva Veda, with all the other sacred

sciences, disappeared; though the full tradition is said to

survive among the mysterious sages (rishis) who dwell in

Himalayan caves.

When the representatives of the old order, who had been able

to maintain their tradition under ground through the centuries

of persecution, arose again, their intellectual and cultural

superiority was in many fields so great that Buddhism was

defeated. In hardly more than a few decades, Buddhism, by the

mere strength of intellectual argument, was wiped out from the

whole Indian continent over which it had ruled for a thousand

years. It was then (during 6th and 7th

century) that an attempt was made, under the leadership of

Shankaracharya, to restore Hindu culture to its ancient basis.

Megh

raga.

Watch

Raga

Unveiled:

India

’s Voice – A film

The history and essence of North Indian classical Music

***

A number of eminent Brahmins were entrusted with the task of

recovering or re-writing the fundamental treatises on the

traditional sciences. For this they followed the ancient system

which starts from a metaphysical theory whose principles are

common to all aspects of the universe, and works out their

application in a particular domain. In this way the theory of

music was reconstructed. In this way the theory of music was

reconstructed.

Musical theory and theory of language had been considered

from the earliest times as two parallel branches of one general

science of sound. Both had often been codified by the same

writers. The names of Vashishtha,

Yajnavalkya, Narada, Kashyapa, Panini are mentioned

among these early musicologist-grammarians. Nandikeshvara

was celebrated at the same time as the author of a work on the

philosophy of language and of a parallel work on music. His work

on language is believed to be far anterior to the Mahabhashya of

Patanjali (attributed to the 2nd century B.C.) into

which it is usually incorporated, though it is thought to be

probably posterior to Panini, who lived no later than 6th

century B.C. The chronology of works on music would seem,

however, to place both Panini and Nandikeshvara at a much

earlier date. The work of Nandikeshvara on the philosophy of

music is now believed to be lost but fragments of it are

undoubtedly incorporated in later works. At the time of the

Buddhist ascendancy, when so much of the ancient lore had to be

abandoned, grammatical works were considered more important than

musical ones.

A part of Nandikeshvara’s work on dancing, the Abhinaya

Darpana, has been printed (Calcutta 1934) with

English translation by M. Ghosh). An earlier translation by

Ananda Coomaraswamy appeared under the title The Mirror of

Gesture (Harvard Univ. Press. 1917).

Top

of Page

The period extending from the Mahabharata war to the

beginnings of Buddhism may well have been one of the greatest

the culture of India has known, and its influence extended then

(as indeed it still did much later) from the Mediterranean to

China. Traces of its Mediterranean aspect have been found in the

Cretan and Mycenean remains as well as in Egypt and the Middle

East.

The Vedas, which until the beginning of this period had been

transmitted orally, were then written down, and later on, the

Epics and Puranas. Most of the treatises on the ancient sciences

also belong to the age, though many may have been to a certain

extent re-shaped later on. Ananada K. Coomaraswamy, in his book,

Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon, speaks of this “early

Asiatic culture and as far south as Ceylon….in the second

millennium B.C..”

The ancient Kinnari Vina

or Kin, for example, became known in China as the Khin, a

stringed instrument said to have been played by the first

Emperor, Fu-Hi (circa 3000 BC), The Kin is further mentioned in

ancient Chinese chronicles such as the Chi Ki (2nd

century B.C) in reference to events of the 6th or 7th

century. According to the Li Ki, Confucius (551-478) always had

his Khin with him at home, and carried it when he went for a

walk or on a journey.

In Genesis, (iv, 21 and xxxi, 27) a stringed instrument of

the same kind is called Kinnor. David used to play the Kinnor as

well as the nebel (flute).

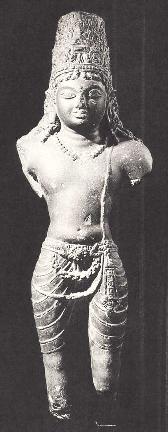

Shiva,

Yoga-Dakshinamurti with Rishis, Snake dancers, and Musicians

- The Art Institute of Chicago.

***

The antiquity of Indian theatrical art and musical theory was

well known to the ancient world. According to Strabo

(Geography X, II 17) the Greeks considered that music,

“from the triple point of view of melody, rhythm and

instruments” came to them originally from Thrace and Asia.

“Besides, the poets, who make of the whole of Asia, including

India, the land or sacred territory of Dionysos, claim that the

origin of music is almost entirely Asiatic. Thus, one of them,

speaking of the lyre, will say, that he causes the strings of

the Asiatic cithara to vibrate.” Many ancient historians spoke

of Dionysos (or Bacchos) as having lived in India.

The many stories that tell how the various styles of North

Indian music were invented by musicians of the Muhammadan period

have probably no basis in reality.

Under Muslim rule, age-old stories were retold as if they had

happened at the court of Akbar, simply to make them more vivid,

and in conformity with the fashion of the day. Such

transferences of legend are frequent everywhere. In Western

countries, many a pagan god in this way became a Christian saint

and many ancient legends were rearranged to fit into Christian

world. Some episodes in the life of the Buddha, for example,

found their way into the Lives of the Saints where the Buddha

appears under the name of St. Josaphat.

The impartial ear of sound-measuring instruments makes one

marvel at the wonderful accuracy of the scales used by the great

“Ustads” of Northern India – scales

which in everyway confirm with the requirements of ancient Hindu

theory.

To say that they pertain to, or have been influenced by, the

Arab or the Persian system shows a very superficial knowledge of

the subject. These systems, originally mostly derived from

Indian music, have become so reduced and impoverished in

comparison with it that no one can seriously speak of their

having had any influence on its development. In fact the whole

of the theory and most of the practice of Arab as well as

Persian music is the direct descendant of the ancient Turkish

music. At the beginning of the Muslim era, the Arabs themselves

had hardly any musical system worth the mentioning, and all the

Arabic theoreticians – Avicenna, (born about 980 A. D)

Al Farabi, Safi ud’din, and others – are claimed by

the Turks as Turkish in culture if not always in race. In fact,

they merely expounded in Arabic the old Turkish system was well

known to medieval Hindu scholars who often mention it (under the

name of Turushka) as a system closely allied to Hindu music. The

seventeen intervals of the octave, as used by the Arabs, are

identical with seventeen of the twenty-two Indian shrutis, and

there is no modal form in Arabic music which is not known to the

Hindus.

(source: Northern

Indian Music -

By Alain Danielou Praeger, 1969 volume I p. 1-35).

Top

of Page

The

Development of Scale

All music is

based upon relations between sounds. These relations can,

however, be worked out in different ways, giving rise to

different groups of musical systems. The modal group of musical

systems, to which practically the whole of Indian muisc belongs,

is based on the establishment of relations between diverse

successive sounds or notes on the one hand and, on the other,

upon a permanent sound fixed and invariable, the

"tonic".

Indian music like all modal

music, thus exists only by the relations of each note with the

tonic. Contrary to common belief, modal music is not merely

melody without accompaniment, nor has a song or melody, in itself,

anything to do with mode. The modes used in the music of the

Christian Church are modes only in name, though they may have been

real modes originally. But much of Scottish and Irish music, for

example, is truly modal; it belongs to the same musical family as

Indian music and is independent of the Western harmonic

system. Indian music like all modal

music, thus exists only by the relations of each note with the

tonic. Contrary to common belief, modal music is not merely

melody without accompaniment, nor has a song or melody, in itself,

anything to do with mode. The modes used in the music of the

Christian Church are modes only in name, though they may have been

real modes originally. But much of Scottish and Irish music, for

example, is truly modal; it belongs to the same musical family as

Indian music and is independent of the Western harmonic

system.

Music must have

been cultivated in very early ages by the Hindus; as the

abridged names of the seven notes, via, sa,

ri, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni, are said to occur in the

Sama Veda; and in their present order. Their names at length are

as follows:

Shadja,

Rishabha, Gandhara, Madhyama, Panchama, Dhaivata, Nishada.

The seven notes

are placed under the protection of seven Ah'hisht'hatri Devatas,

or superintenting divinities as follows:

Shadja, under

the protection of Agni

Rishabha, of Brahma

Gandhara, of Saraswati

Madhyama, of Mahadeva

Panchama, of Sri or Lakshmi

Dhaivata, of Ganesa

Nishada, of Surya

"The note

Sa is said to be the soul, Ri is called the head, Ga is the

arms, Ma the chest, Pa the throat, Dha the hips, Ni the feet.

Such are the seven limbs of the modal scale." (Narada

Samhita 2, 53-54).

"Shadja is

the first of all the notes and so it is the main or chief

note." Datilla explains that the Shadja (the tonic)

may be established at will at any pitch (on any shruti) and that,

by relation with it, the other notes should be established at the

proper intervals.

The Hindus

divide the octave into twenty two intervals, which are called

Sruti, by allocating four Sruti to represent the interval. The

sruti or microtonal interval is a division of the semitone, but

not necessarily an equal division. This division of the semitone

is found also in ancient Greek music. It is an interesting fact

that we find in Greek music the counterpart of many things in

Indian music. Ancient India divided the octave into twenty two and

the Greek into twenty-four. The two earliest Greek scales, the

Mixolydic and the Doric show affinity with early Indian scales.

The Indian scale divides the octave into twenty-two srutis.

Gramas

Indian

music is traditionally based on the three gramas. First reference

to Grammas or ancient scales is found in the Mahabharata and teh

Harivamsa. The former speaks of the 'sweet note Gandhara',

probably referring to the scale of that name. The Harivamsa speaks

enthusiastically of music 'in the gramaraga which goes down to

Gandhara', and ot 'the women of Bhima's race who performed, in the

Gandhara gramaraga, the descent of the Ganges, so as to delight

mind and ear.'

Top

of Page

The

Nature of Sound

"Sound

(Nada) is the treasure of happiness for the happy, the

distraction of those who suffer, the winner of the hearts of

hearers, distraction of those who suffer, the winner of the

hearts of hearers, the first messenger of the God of Love. It is

the clever and easily obtained beloved of passionate women. May

it ever, ever, be honored. It is the fifth approach to Eternal

Wisdom, the Veda."

- Sangita Bhashya.

Sound is said

to be of two kinds, one a vibration of ether, the other a

vibration of air. The vibration of ether, which remains

unperceived by the physical sense, is considered the principle

of all manifestation, the basis of all substance. It corresponds

with what Pythagoras called the "music of the spheres"

and forms permanent numerical patterns which lie at the very

root of the world's existence. This kind of vibration is not due

to any physical shock, as are all audible sounds. It is

therefore called anahata, "unstruck".

The other kind of sound is an impermanent vibration of the air,

an image of the ether vibration of the same frequency. It is

audible, and is always produced by a shock. It is therefore

called ahata or "struck".

Watch

Raga

Unveiled:

India

’s Voice – A film

The history and essence of North Indian classical Music

***

Thus, the Sangita

Makaranda (I 4-6) says: "Sound is considered to

be of two kinds, unstruck and and struck; of these two, the

unstruck will be first described. "Sound produced from

ether is known as 'unstruck'. In this unstruck sound the Gods

delight. The Yogis, the Great Spirits, projecting their minds by

an effort of the mind into this unstruck sound, depart,

attaining Liberation."

"Struck

sound is said to give pleasure, 'unstruck' sound gives

Liberation." (Narada Purana).

But "this

(unstruck sound) having no relation with human enjoyment does

not interest ordinary men." (Sang. Ratn 6.7.12).

Top

of Page

Raga

- The Basis of Melody

"I

don not dwell in heaven, nor in the heart of yogis. there only I

abide, O Narada, where my lovers sing."

(Narada Samhita I.7).

"That

which charms is a raga." (Sang.

Darpan 2-1).

Each

raga or mode of Indian music is a set of given sounds called notes

(svara-s) forming with a permanent tonic certain ratios. To each

of these ratios is said to correspond a definite idea or emotion.

The complex mood created by the mixture and contrast of these

different ideas or emotions is the mood or expression of the raga.

The harmonious relations which exist between the notes and which

can be represented by numerical ratios do not exclusively belong

to music. The very same relations can be found in the harmony

which binds together all the aspects of manifestation. These

ratios can express the change of the seasons and that of the

hours, the symphony of colors as well as that of forms. Hence the

mood of a raga can be accurately represented by a picture or a

poem which only creates an equivalent harmony through another

medium. The expression of a raga is thus determined by its scale.

It results from the expressions of each of the intervals (shrutis)

which the different notes form with the tonic.

The

Raga poems: Poems describing the mood of the raga are found in a

number of Sanskrit works of music. References

to them in other works seem to show that many of them were

originally part of a treatise (now believed lost) by Kohala, one

of the earliest writers on music.

Raga is the

basis of melody in Indian music and a substitute for the western

scale. "It is the attempt of an

artistic nation to reduce the law and order the melodies that

come and go on the lips of the people." In Raga

Vibodha, it is defined as 'an arrangement of sounds which

possesses varna, (color) funishes gratification to the

senses and is constituted by musical notes." says Matanga.

Indian ragas

are also supposed to be able to reproduce the conditions and

emotions associated with them. The Dipak

raga is supposed to produce flames in actuality; and

a story is told of the famous musician named Gopal

Naik (Baiju Bawara) who, when ordered to sing this by

the Emperor Akbar went and stood in the Jamuna up to his neck

and then started the song. The water became gradually hotter

until flames burst out of his body and he was consumed to ashes.

The Megh mallar raga is

supposed to be able to produce rain. It is said that a dancing

girl in Bengal, in a time of drought, once drew from the clouds

with this raga a timely refreshing shower which saved the rice

crop. Sir W. Ousley, who

relates many of these anecdotes, says that he was told by Bengal

people that this power of reproducing the actual conditions of

the raga is now only possessed by some musicians in western

India.

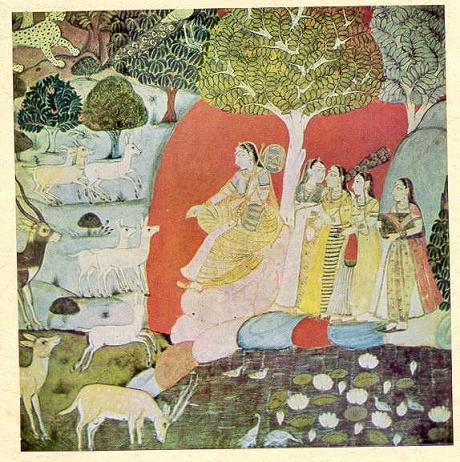

In connection

with the sciences of raga, Indian music has developed the art of

raga pictures. Mr. Percy Brown,

formerly of the School of Art, Calcutta, defines a raga as "a

work of art in which the tune, the song, the picture, the

colors, the season, the hour and the virtues are so blended

together as to produce a composite production to which the West

can furnish no parallel."

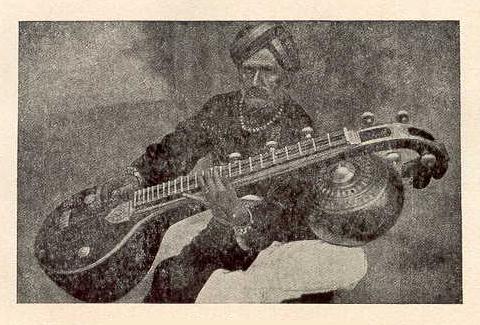

Vina

player from Mysore.

***

It may be

described as a musical movement, which is not only represented

by sound, but also by a picture. Rajah

S M Tagore, thus describes the pictorial

representations of his six principal ragas. Sriraga

is represented as a divine being wandering through a beautiful

grove with his love, gathering fragrant flowers as they pass

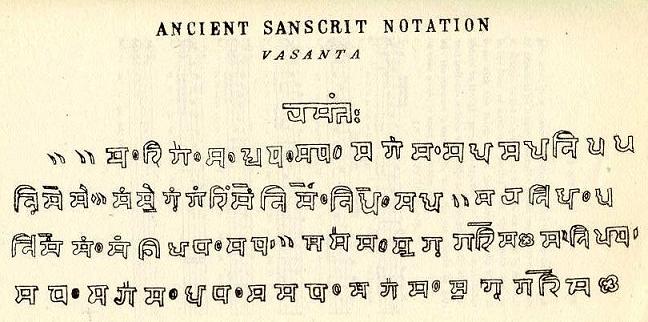

along. Near by doves sport on the grassy sward. Vasanta

raga, or the raga of spring, is represented as a

young man of golden hue, and having his ears ornamented with

mango blossoms, some of which he also holds in his hands. His

lotus-like eyes are rolling round and are of the color of the

rising sun. He is loved by the females. Bhairava

is shown as the great Mahadeva (Shiva) seated as a sage on a

mountain top. River Ganga falls upon his matted locks. His head

is adorned with the crescent moon. In the center of his forehead

is the third eye from which issued the flames which reduced Kama,

the Indian Cupid, to ashes. Serpents twine around his neck. He

holds a trident in one hand and a drum in the other. Before him

stands his sacred bull - Nandi. Panchama

raga is pictured as a very young couple in love in a

forest. Megh raga is the

raga of the clouds, and the rainy season. It is the raga of hope

and new life. The clouds hang overhead, and already some drops

of rain have fallen. The animals in the fields rejoice. This

raga is said to be helpful for patients suffering from

tuberculosis. Nattanarayana

is the raga of battle. A warrior king rides on a galloping steed

over the field of battle, with lance and bow and shield. Lakshmana

Pillay has said: "Thus, each raga comes and goes

with its store of smiles or tears, of passion or pathos, its

noble and lofty impulses, and leaves its mark on the mind of the

hearer."

Sir Percy Brown read a paper

on the raga which he called Visualized

Music. He described it as a combination of two arts,

music and painting. He mentioned a miniature painting which was

called 'the fifth delineation of the melody Megh

Mallar Saranga, played in four-time at the time of

the spring rains. He wrote: "Todi ragini is one of the

brides of Vasanta raga. The melody of this raga is so

fascinating that every living creature within hearing is

attracted to it. as the raga has to be performed at

midday."

This

art seems to have come originally from northwest India. The

Indian tendency is to visualize abstract things.

The

six principal ragas are the following:

1.

Hindaul - It is played to

produce on the mind of the bearer all the sweetness and freshness

of spring; sweet as the honey of the bee and fragrant as the

perfume of a thousand blossoms.

2. Sri

Raga - The quality of this rag is to affect the mind

with the calmness and silence of declining day, to tinge the

thoughts with a roseate hue, as clouds are glided by the setting

sun before the approach of darkness and night.

3. Megh

Mallar - This is descriptive of the effects of an

approaching thunder-storm and rain, having the power of

influencing clouds in time of drought.

4. Deepak

- This raga is extinct. No one could sing it and live; it has

consequently fallen into disuse. Its effect is to light the lamps

and to cause the body of the singer to produce flames by which he

dies.

5. Bhairava

- The effect of this rag is to inspire the mind with a feeling of

approaching dawn, the caroling of birds, the sweetness of the

perfume and the air, the sparkling freshness of dew-dropping morn.

6. Malkos

- The effect of this rag are to produce on the mind a feeling of

gentle stimulation.

(source:

Hindu

Superiority - By Har Bilas Sarda

p. 371).

Top

of Page

Tala

or Time Measure

Claude

Alvares has written: "The Indian system of talas, the rhythmical time-scale of Indian

classical music, has been shown (by contemporary analytical

methods) to possess an extreme

mathematical complexity. The basis of the system is

not conventional arithmetic, however, but more akin to what is

known today as pattern recognition."

To

quote Richard Lannoy author

of The

Speaking Tree:

A Study of Indian Culture and Society:

"In

the hands of a virtuoso the talas are played at a speed so fast

that the audience cannot possibly have time to count the

intervals; due to the speed at which they are played, the talas

are registered in the brain as a cluster configuration, a

complex Gestalt involving all the senses at once. While the

structure of the talas can be laboriously reduced to a

mathematical sequence, the effect is subjective and

emotional.....The audience at a recital of Indian classical

music becomes physically engrossed by the agile patterns and

counter-patterns, responding with unfailing and instinctive kinesthetic

accuracy to the terminal beat in each tala."

Their

ability with instruments is repeated with the voice. The

extraordinary degree of control of the human voice has been

described by the musicologist, Alain Danielou, who has stated

that Indian musicians can produce and differentiate between

minute intervals (exact to a hundreth of a comma, according to

identical measurements recorded by Danielou at monthly recording

sessions). This sensitivity to microtones is, from the purely

musicological point of view, of little importance, like the

mathematical complexity of the talas. Nevertheless, as Lannoy

puts it: Their

ability with instruments is repeated with the voice. The

extraordinary degree of control of the human voice has been

described by the musicologist, Alain Danielou, who has stated

that Indian musicians can produce and differentiate between

minute intervals (exact to a hundreth of a comma, according to

identical measurements recorded by Danielou at monthly recording

sessions). This sensitivity to microtones is, from the purely

musicological point of view, of little importance, like the

mathematical complexity of the talas. Nevertheless, as Lannoy

puts it:

"It

is an indication of the care with which the "culture of

sound" is developed, for Hindus still believe that such

precision in the repetition of exact intervals, over and over

again, permits sounds to act upon the internal personality,

transform sensibility, way of thinking, state of soul, and even

moral character."

(source:

Decolonizing

History: Technology and Culture in India, China and the West

1492 to the Present Day - By Claude Alvares p.

73-74).

"In

other words, the Hindu has never divorced

the physical from the spiritual; these 'ancient

physiologists' ascribed an ethical significance to physiological

sensitivity. The aristocratic cult of kalokagathia, 'beautiful

goodness', has never been abandoned in India, even if its

metaphysic bears little resemblance to the kalokagathia of the

ancient Greeks.

(source: The

Speaking Tree:

A Study of Indian Culture and Society

- By Richard Lannoy p. 275).

Musical time in

India, more obviously then elsewhere, is a development from the

prosody and metres of poetry. The insistent demands of language

and the idiosyncrasies of highly characteristic verse haunt the

music, like a 'presence which is not to be put by.' 'The

time-relations of music are affected both by the structure of

the language and by the method of versification which ultimately

derives from it.' says one student of Indian music from the west.

Until late, there was practically no prose in India and

everything had to be learnt through the medium of verse chanted

to regular rules. Both in Sanskrit and in the vernacular all

syllables are classified according to their time-lengths, the

unit of time being a matra. Very short syllables of less than a

matra also occur.

Great stress

has always been laid by Indian grammarians upon giving 'the

exact value' to syllables inverse; and as there is no accent at

all in Indian verse the time-length is all important. This

may account for the great development of time-measures in Indian

music. Rajah S M Tagore says that the word tala

refers to the beating of time by the clapping of hands.

Sometimes it is also done by means of small hand-cymbals, which

are called tala or kaitala or kartal (hand-cymbals).

Top

of Page

Musical Instruments

and Sanskrit

Writers on Music

The Vedic

Index shows a very wide variety of musical

instruments in use in Vedic times. Instruments of percussion are

represented by the dundubhi,

an ordinary drum; the adambara,

another kind of drum, bhumidundubhi,

an earthdrum made by digging a hole in the ground covering it

with hide; vanaspati, a

wooden drum; aghati, a

cymbal used to accompany dancing. Stringed instruments are

represented by the kanda-vina,

akind of lute; karkari,

another lute; vana, a lute

of 100 strings; and the vina,

the present instrument of that name in India. This

one instrument alone is sufficient evidence of the development

to which the art had attained even in those early days. There

are also a number of wind instruments of the flute variety, such

as the tunava, a wooden flute; the nadi, a reed flute, bakura,

whose exact shape is unknown. 'By the time of the Yajur Veda

several kinds of professional musicians appear to have arisen;

for lute-players, drummers, flute-players, and conch-blowers are

mentioned in the list of callings.'

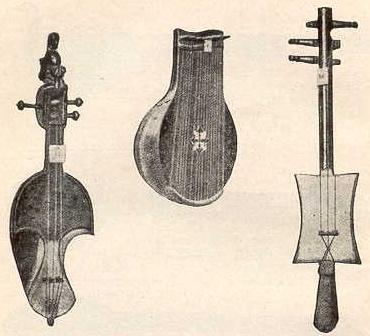

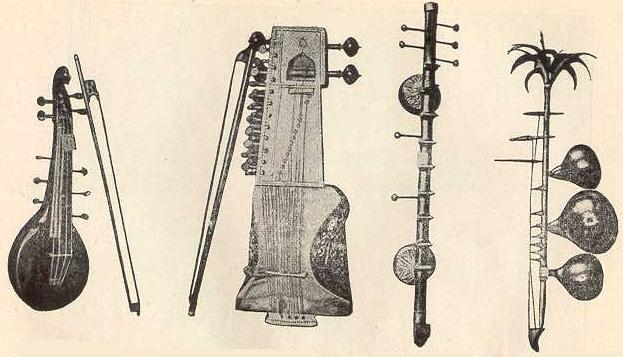

Kalyayana-vina

Sarinda

Katyayana-vina

Chikara

That vocal

music had already got beyond the primitive stage may be

concluded from the somewhat complicated method of chanting the Sama

Veda, which goes back to the Aryan age. These hymns

of the Rig Veda and Sama Veda are the earliest examples we have

of words set to music. The Sama Veda, was sung according to very

strict rules, and present day Samagah - temple singers of the

Saman - claim that the oral tradition which they have received

goes back to those ancient times. The Chandogya and the

Brihadaranyaka Upanishads both mention the singing of the Sama

Veda and the latter also refers to a number of musical

instruments.

Sarangi

(Bengal)

Sarangi

Mahati Vina

Kinnari

Mayuri Esraj

Vina (Southern)

Ektar

Group

of stringed instruments: Dilruba, Bin Sarangi and Peacock

sitar Some ancient instruments:

Svaramandala. Brahma cina, Kural and Bastram.

Watch

Raga

Unveiled:

India

’s Voice – A film

The history and essence of North Indian classical Music

***

Drumming

The

drum is one of the most important of Indian musical instruments.

It provides the tonic to which all the other instruments must be

tuned. It is a royal instrument having the right of royal honors.

The drums used in India are innumerable. Mrs.

Mann says: "The Indian drummer is a great artist.

He will play a rhythm concerto all alone and play us into an ecstasy

with it." "The drummer will play it in bars of 10, 13,

16, or 20 beats, with divisions within each bar flung out with a

marvelous hypnotizing swing. Suggestions of such rhythm beaten out

by a ragged urchin on the end of an empty kerosene oil-can first

aroused me to the beauty and power of Indian music."

The

Indian drummer can obtain the most fascinating rhythm from a mud

pot, and some of them are great experts at this pot-drumming. The mridanga

and tabla are both played in

the same way, the only difference being that, in the case of the

table, the two heads are on two small drums, and not on the same

drum. The Mridanga or Mardala

is the most common and probably the most ancient of Indian drums.

It is said to be invented by Brahma to serve as an accompaniment

to the dance of Shiva, in the honor of his victory over

Tripurasura; and Ganesha, his son, is said to have been the first

one play upon it. The word Mridanga or Mardala means 'made of

clay' and probably therefore its body was originally of mud. Other

drums include Pakhawaj, Nagara or Bheri or Nakkara, Dundubhi

Mahanagar or Nahabet, Karadsamila, Dhol, Dhoki, Dholak and Dak.

Damaru, Nidukku, or Budhudaka, Udukku, Edaka and many others.

***

In the Ramayana

mention is frequently made of the singing

of ballads, which argues very considerable

development of the art of music. The poem composed by the sage

Valmiki is said to have been sung before King Dasratha. The

Ramayana often makes use of musical similes. The humming of the

bees reminded him of the music of stringed instruments, and the

thunder of the clouds of the beating of the mridanga. He talks

of the music of the battlefield, in which the twanging and

creaking of the bows takes the place of stringed instruments and

vocal music is supplied by the low moaning of the

elephants. Ravana is made to say that "he will play

upon the lute of his terrific bow with the sticks of his

arrows." Ravana was a great master of music and was said to

have appeased Shiva by his sublime chanting of Vedic hymns.

The Mahabharata

speaks of seven Svaras and also of the Gandhara Grama, the

ancient third mode. The theory of consonance is also alluded

to.

The Mahajanaka

Jataka (c. 200 B. C) mentions the four great sound (parama maha

sabda) which are conferred as an honor by the Hindu kings on

great personages. In these drums is associated with various

kinds of horn, gong and cymbals. These were sounded in front of

a chariot which was occupied, but behind one which was empty.

The car used to go slowly round the palace and up what was

called 'the kettle-drum road'. At such a time they sounded

hundreds of instruments so that 'it was like the noise of the

sea.' The Jataka also records how Brahmadatta presented a

mountain hermit with a drum, telling him that if he beat on one

side his enemies would run away and if upon the other they would

become his firm friends.

In the Tamil

books Purananuru and Pattupattu

(c. A.D 100-200) the drum is referred to as occupying a position

of very great honor. It had a special seat called murasukattil,

and a special elephant, and was treated almost as a deity. It is

described as 'adorned with a garland like the rainbow.' One of

the poets tells us, marveling at the mercy of the king, 'how he

sat unwittingly upon the drum couch and yet was not

punished.' Three kinds of drums are mentioned in these

books: the battle drum, the judgment drum and the sacrificial

drum. The battle drum was regarded with same the veneration that

regiments used to bestow upon the regimental flag. One poem

likens the beating of the drum to the sound of a mountain

torrent. Another thus celebrates the virtues of the drummer. In the Tamil

books Purananuru and Pattupattu

(c. A.D 100-200) the drum is referred to as occupying a position

of very great honor. It had a special seat called murasukattil,

and a special elephant, and was treated almost as a deity. It is

described as 'adorned with a garland like the rainbow.' One of

the poets tells us, marveling at the mercy of the king, 'how he

sat unwittingly upon the drum couch and yet was not

punished.' Three kinds of drums are mentioned in these

books: the battle drum, the judgment drum and the sacrificial

drum. The battle drum was regarded with same the veneration that

regiments used to bestow upon the regimental flag. One poem

likens the beating of the drum to the sound of a mountain

torrent. Another thus celebrates the virtues of the drummer.

"For my

grandsire's grandsire, his grandsire's grandsire.

Beat the drum. For my father, his father did the same.

So he for me. From duties of his clan be has not swerved.

Pour forth for him one other cup of palm tree's purest

wine.."

The early Tamil

literature makes much mention of music. The Paripadal

(c. A.D 100-200) gives the names of some of the svaras and

mentions the fact of there being seven Palai (ancient modes).

The yal is the peculiar instrument of the ancient Tamil land. No

specimen of it still exists today. It was evidently something

like the vina but not the same instrument, as the poet Manikkavachakar

(c. A. D 500-700) mentions both in such a way as to indicate two

different instruments. Some of its varieties are said to have

had over 1,000 strings. The The Silappadigaram

(A. D. 300), a Buddhist drama, mentions the drummer, the flute

player, and the vina as well as the yal, and also has specimens

of early Tamil songs. This book contains some of the

earliest expositions of the Indian musical scale, giving the

seven notes of the gamut and also a number of the modes and

ragas in use at that time. The latter centuries of the Buddhist

period were more fertile in architecture, sculpture and painting

than in music. The dramas of Kalidasa

make frequent references to music and evidently the rajahs of

the time had regular musicians attached to their courts. In the Malavikagnimitra

a song in four-time is mentioned as a great feat performed at a

contest between two musicians. The development of the drama

after Kalidasa meant the development of music as well, as all

Indian drama is operatic. 'The temple and the stage were the

great schools of Indian music.'

The oldest

detailed exposition of Indian musical theory which has survived

the ravages of ants and the fury of men is found in a treatise

called Natya Sastra or the

science of dancing, said to have been composed by the sage

Bharata. There are nine chapters of the Natya Sashtra

that deal with music proper. These contain a detailed exposition

of the svaras, srutis, gramas, murohhansas, jatis. A translation

of a portion of this chapter appeared in Mr. Clement's

Introduction to Indian Music, and there is a complete French

translation by Jean Grosset.

The seventh and

eighth centuries of our era in South India witnessed a religious

revival associated with the bhakti

movement and connected with the theistic and popular

sects of Vishnu and Shiva. This revival was spread far and wide

by means of songs composed by the leaders of the movement and so

resulted in a great development of musical activity among the

people generally and in the spread of musical education. Sangita

Makaranda, said to be by Narada, but not Narada Rishi as his

name is mentioned in the book, was probably composed between the

eighth and eleventh centuries. He gives a similar account of the

Gandhara Grama to that of Sangita Ratnakara. Musical sounds are

divided into five classes according to the agency of

productions, as nails, wind etc. The 18 Jatis of Bharata are

given and he enumerates 93 ragas.

***

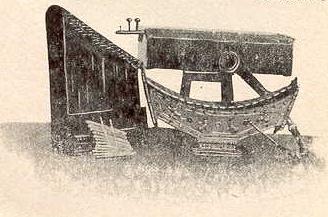

In

Shiva’s temple, stone pillars make music - an architectural

rarity

Shiva

is the Destroyer and Lord of Rhythm in the Hindu trinity. But here

he is Lord Nellaiyappar, the Protector of Paddy, as the name of

the town itself testifies — nel meaning paddy and veli meaning

fence in Tamil.

Prefixed

to nelveli is tiru, which signifies something special — like the

exceptional role of the Lord of Rhythm

or the unique musical stone pillars in the temple.In the Nellaiyappar

temple, gentle taps on the cluster of columns hewn out of a single

piece of rock can produce the keynotes of Indian classical music.

“Hardly

anybody knows the intricacies of how these were constructed to

resonate a certain frequency. The more aesthetically inclined with

some musical knowledge can bring out the rudiments of some rare

ragas from these pillars.”

The

Nelliyappar temple chronicle, Thirukovil Varalaaru, says the

nadaththai ezhuppum kal thoongal — stone

pillars that produce music — were set in place in the 7th

century during the reign of Pandyan king Nindraseer Nedumaran.

Archaeologists

date the temple before 7th century and say it was built by

successive rulers of the Pandyan dynasty that ruled over the

southern parts of Tamil Nadu from Madurai. Tirunelveli, about 150

km south of Madurai, served as their subsidiary capital.

Each

huge musical pillar carved from one piece of rock comprises a

cluster of smaller columns and stands testimony to a unique

understanding of the “physics and mathematics of sound." Well-known

music researcher and scholar Prof. Sambamurthy Shastry, the “marvellous

musical stone pillars” are “without a parallel” in any other

part of the country.

“What

is unique about the musical stone pillars in the Tiruelveli

Nellaiyappar temple is the fact you have a cluster as large as 48

musical pillars carved from one piece of stone, a delight to both

the ears and the eyes,” The

pillars at the Nellaiyappar temple are a combination of the Shruti

and Laya types. This

is an architectural rarity and a sublime beauty to be cherished

and preserved.

(source: In

Shiva’s temple, pillars make music - telegraphindia.com).

Top

of Page

Some

Ancient

Musical Authorities

Among important

landmarks of the literature on music must also be counted

portions of certain Puranas, particularly the Vishnu Dharmottara,

Markandeya Purana and Vayu

Purana. The Hindus claim a great antiquity for these

Puranas and this seems to be corroborated by the technical terms

used in reference to music. The Sanskrit authors on music can be

divided into four main periods. The first period is those whose

names are mentioned in the Puranans and in the Epics (Mahabharata

and Ramayana), the second that of the authors mentioned in the

early medieval works (Buddhistic period), the third period is

that of the authors who wrote between the early medieval Hindu

revival and the Muslim invasion, and the last or modern period

that of Sanskrit writers under Muslim and European rule.

(Note: The

Different Narada -s: There were probably three authors known by

the name of Narada. One, the author of the Naradiya Shiksha. The

Panchama Samhita and Narada Samhita are probably the work of the

later Narada (Narada II), the author of the Sangita Makarnada.

Sanskrit

authors on music can be divided into four main periods, according

to Alain Danielou.

***

First

Period - ((The Vedic/Puranic/Epic Period)

Narada, Bharata,

Nandikeshvara, Arjuna, Matanga, Kohala, Dattila, Matrigupta, and Rudrata and

others.

Second

Period

Abhinava

Gupta, Sharadatanaya, Nanya Bhupala, Parshvadeva and

Sharngadeva, and others.

Third

Period

Udbhata,

Lollata, Shankuka, Utpala Deva, Nrisimha Gupta, Bhoja King,

Simhana, Abhaya Deva, Mammata, Rudrasena, Someshvara

II, Lochana Kavi (Raga Tarangini), Sharngadeva (Sangita

Ratnakara), Jayasimha, Ganapati, Jayasena, Hammira, Gopala Nayak

and others.

Fourth

Period

Harinayaka,

Meshakarna, Madanapala Deva, Ramamatya (Svara-mela Kalanidhi), Somanatha (Raga Vibodha), Damodhara Mishra (Sangita

Darpana), Pundarika Vitthala (Shadraga Chandrodya, Raga Mala,

Raga Manjari), Somanatha, Govinda Dikshita, Basava Raja,

and others.

***

The first North

Indian musician whom we can definitely locate both in time and

place is Jayadeva, who lived

at the end of the 12th century. He was born at Kendula near

Bolpur, where lived Rabindranath Tagore, the poet, laureate of

Bengal and modern India. Jayadeve wrote and sang the Gita

Govinda, a series of songs descriptive of the love of

Krishna, and the bhakti movement. The Gita Govinda was

translated by Sir Edwin Arnold under the name of The Indian Song

of Songs. In these songs Radha pours forth her yearning, her

sorrow and her joy and Krishna assures her of his love.

Sarangadeva

- (1210- 1247 A D) one of the greatest of ancient Indian musical

authorities and one who still inspires reverence in the minds of

India's musicians. He lived at the court of the Yadava dynasty

of Devagiri in the Deccan. at that time the Maratha Empire

extended to the river Kaveri in the south, and it is probable

that Sarngadeva had come into contact with the music of the

south as well as the north. His work, the Sangita Ratnakara

shows many signs of this contact. It is possible that he was

endeavoring to give the common theory which underlies both

systems.